As with so many of our Sunday readings, there is again a connection between the first reading from Sirach, in this case, and the gospel passage from Matthew. Both readings are about forgiveness and also about vengeance, which lingers an inch below the surface in even the most forgiving person. Of course, it’s always easier to speak about forgiveness than to live it. To the degree that we know we need forgiveness and to the degree we actively receive it, to that degree we can pass forgiveness on to others. If you’ve never been in need of forgiveness, you likely don’t know how terrible it feels to be unforgiven. You’re not motivated or inspired to free others unless you know how wonderful it is to be liberated in love yourself. Without forgiveness, there is nothing new under the sun; it’s all a tit-for-tat world. Without forgiveness, everything comes to a grinding halt, and we all end up living in our own insulated world of justifying why we are right and why others are wrong.

Every time we do forgive, it’s actually a breakdown of logic. When you hurt me, I deserve, no I demand, that you give me something to make up for it; that’s the world of logic, fairness and justice. I’m expecting to receive something, but the gospel compels me to give something instead, to give forgiveness to the one who hurt me. Forgiveness breaks down the logic that frames our very lives, a logic that says, “I deserve, and you owe me.” Every time God forgives, God is breaking God’s own rules and saying, “I would rather be in relationship with you than be right!”

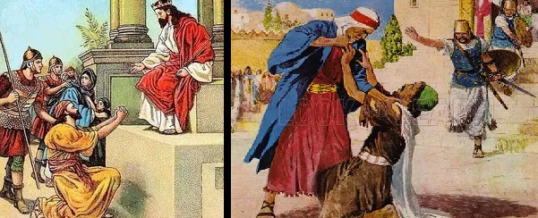

Before Jesus gets into the parable of the king and the unforgiving slave, he has a real question on the floor to deal with. Peter’s question is, “Lord, how often should I forgive my brother or sister if they have sinned against me? As many as seven times?” I find seven times is a very generous offer. On an exceptionally good day, I might be able to go two and a half times, which is nowhere near seven. What’s underneath Peter’s question is, “When can I stop? When can I get even?” If I forgive the person seven times, on the eight time can I really let them have it? Jesus answers the question with a figure of speech, not a mathematical formula. He says, “Not seven time, but, I tell you, 77 times.” Again, we are not to presume that on the 78th offense we can get our revenge. It is a figure of speech used by Jesus to tell us, “You can never stop forgiving.” Why? Because in Jesus’ way of framing life and forgiveness there are only two spirals: the spiral of forgiveness and the spiral of vengeance. The moment you exit the spiral of forgiveness, even for the shortest of time, you immediately enter into the spiral of vengeance and violence. It’s that fast. Vengeance is a knee-jerk reaction in all of us, and it sets off a chain reaction, a runaway train you might say, that’s very hard to stop. The only thing that can stop the spiral of vengeance and violence is forgiveness.

In the parable a slave owes the king 10, 000 talents. After asking for time to pay it back, the king extends mercy to him and forgives this slave the entire debt. In the process of leaving the king’s presence–that’s how fast it happens–this very slave comes upon a second slave who owes him 100 denarii. The first slave immediately grabs the second slave by the throat and demands he repay him the 100 denarii. The second slave uses the exact same words as the first slave used with the king, “Have patience with me, and I will repay you everything.” The first slave shows no patience, no mercy, no forgiveness. Instead, he has the second slave thrown into prison until he would pay the debt. If we transferred the 10, 000 talents the first slave owed the king and the 100 denarii the second slave owed the first slave, into equivalent dollars, the story would go something like this. The first slave is forgiven a debt of $600, 000. Yet, when he comes upon a second slave who owes him the equivalent of $1, he immediately throttles him and has him arrested.

Peter, do you now know why you must forgive 77 times? Peter, do you now know why you can’t stop forgiving? The moment you stop forgiving, you have your hands around someone else’s neck. The moment you leave the spiral of forgiveness, you enter the world or vengeance and violence. It’s that fast. As the slave went out of the king’s palace, not two weeks later, he’s immediately in the world of vengeance.

The ending of this parable is a little bit of a conundrum, a conflict. It may have been written not by the gospel writer, Matthew, but by a later scribe who got upset at God’s generosity. It seems a bit un-Godly that God would not take God’s own advice. In fact, it seems God tortures people if they don’t do it right. The line says, “his lord handed him over to be tortured until he would pay his entire debt.” It really doesn’t fit the overall context of God’s great love. It appears that God is torturing those who don’t forgive. I think Jesus is talking about self-torture. It’s not God who tortures you; we humans torture ourselves and one another and then project that onto God.

The scenario goes something like this. You remember and replay an offense done against you. Each time you remember it, it gets tighter and more hateful. In your mind the offender becomes even more evil and you become more the victim. We’ve all lived in a kind of obsessive-compulsive trap where we keep playing the video over in our mind, trying to decide who is right and who is wrong, who deserves torture and who deserves mercy. What a waste of energy. If you’ve been forgiven a $600, 000 debt, does it really matter that someone owes you $1? I believe the torturer is your own mind, heart and spirit. Holding on to past grievances does you and everyone else no good. If we do not learn to forgive, we’ll never be free. We have to let go or there is no future to anything.

From 1968 to 1998, those 30 years were called the Northern Ireland Conflict. It wasn’t a religious conflict per se, although most people saw it as a war pitting Catholics against Protestants. More properly understood, it was the majority of Protestants who wanted Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom as opposed to a majority of Catholics who wanted Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom and join a united Ireland. Forgetting that “by our love for one another the world will recognize we are Jesus’ disciples,” the fighting and bloodshed continued unabated until the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

In the April 2019 issue of Columbia, the Knights of Columbus magazine, I read a wonderful article about the conflict in Northern Ireland during those 30 troubling years. The article centered on a man named Richard Moore. This Catholic man recalls the day when he was 10 years old and it was 1972. He lost his sight when a British soldier shot him in the face with a rubber bullet.

He writes: “In my young adult years, I began to think about my blindness, about why I’m so happy and contented, and I realized that one very significant reason was because I had no anger or no hatred. Anger is a self-destructive emotion; it destroys you from the inside out, and I didn’t have that.

Many years after that I began to think about forgiveness. Forgiveness is first and foremost a gift that you give to yourself. Forget about the soldier who blinded me; if he wants my forgiveness he has it, but that’s not what’s important. What’s important for my own peace of mind is that I forgive him. So forgiveness isn’t about the perpetrator; it’s about yourself.

The second thing that I realized about forgiveness is it doesn’t change the past, but it does change the future.”

I have since thrown out that magazine, but I do remember a picture of this man sitting with the British soldier who blinded him back in 1972. They’ve both become best friends. That’s why, Peter, you must remain in the spiral of forgiveness and forgive 77 times. For without forgiveness, there’s nothing new under the sun. With forgiveness, everything is new again.

Fr. Phil

SEP

2023

About the Author: