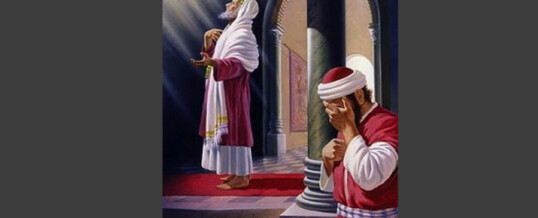

A little story about people who are self-righteous, like the Pharisee who prayed in the Temple.

Jimmy, the local drunk, womanizer, and thief dies. His wife, a proper lady, wants a nice funeral for him to keep up appearances, if for nothing else. So, even though religion meant nothing to Jimmy, his wife, nevertheless, goes to visit the parish priest. “Please,” she begs the priest, “I know Jimmy was a scoundrel and never went to church, but can’t you at least bury him and say a kind word over his body?” The priest looked up at the poor, pleading woman and felt sorry for her. “Oh, all right,” the priest said. “Bring him to the church tomorrow, and I’ll see what I can do.”

The entire town and every one of Jimmy’s relatives, down to his third cousins, turned up at the funeral to hear what good a priest could possibly think to say about a guy like this. The priest took a deep breath, looked over the straining, expectant crowd, thought a moment, and said, “I know Jimmy O’Brien was a drunk, a womanizer, and a thief. But next to the rest of his family, this guy was a saint!”

Without force-fitting the three Scripture readings together, they seemingly overlap, naturally, around a common theme. What jumps out for me, this time around, is the theme of humility. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: I’m naturally attracted to humble people and repelled by arrogant people. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the seesaw battle within myself—the battle between my content, True Self and my never-content, attention-starved Ego. I’m attracted to and want to be more like humble people. These are people who have been humbled, usually by circumstances of life beyond their control. Though, sometimes we are humbled by our own blindness, our own self-centeredness, or our own stupidity. Truly humble people know what it’s like to live at the bottom or the edges of things. It’s at the bottom and the outer edges of life, and not at the top or the comfortable middle, where we learn the most. But being at the bottom or the edges, in and of itself, will not make you a better person nor a humble person. It could make you an angry or bitter person who feels cheated by life.

Ben Sirach, the writer of that first reading, says to us, “He (God) will not show partiality to the poor.” In other words, just because you’re poor, doesn’t mean you are favored by God. We are told in that first reading: with him (God) there is no partiality, no favoritism. (If that’s true, and I believe it is, then I better stop wearing my favorite T-shirt that says: “Jesus loves you, but I’m his favorite.” Either I ditch the shirt, or I ditch the Scriptures. Don’t pressure me…I’m thinking!). If God breaks God’s rule and doesshow partiality to one group, it seems to me that group are the humble. Not the rich nor the poor, not the educated nor the Grade-3 dropout, not the sober nor the alcoholics, not the straight nor the gay, not the gated-community people nor those living in tents—but plainly and simply, it’s the prayers of the humble that pierces the clouds.

Paul was not always St. Paul. Paul spent most of his life as an arrogant, self-righteous Pharisee. He lived at the top of every heap. He followed Jewish law to the tee. He was very much like the proud Pharisee, in the gospel, who goes to the Temple bragging about all the laws he fulfilled, all the boxes he checked off, boxes that most other people—the thieves, adulterers, the tax collectors–were not checking off. Paul, before his conversion, could even justify rounding up and putting many followers of Christ to death. Yet, after he gets knocked to the ground, literally, and temporarily blinded by the light of Christ, he becomes a humble man.

That second reading, Paul’s Letter to Timothy, was written when Paul was at the bottom, the far edge of life. He was imprisoned and close to the end of his life. He says, “At my defense—when I really needed you the most—no one came to my support, but all deserted me.” Talk about humiliation! While he is humbled, he doesn’t become bitter, angry, or blaming. Instead, he asks God to use his humiliation–the humiliation of being imprisoned and powerless, for some greater purpose. Paul asks God to use him, in his powerless-one-down position in prison to reach out to the Gentiles, a group of people who are also powerless and in the one-down position especially compared to the Jews. Paul asked God to use his humility as a tool to reach out to the humble people of the world. The Gentiles (non-Jews) didn’t have the prophets, or the Law, or the long traditions of the Jews, but Paul knew they were just as import in God’s eyes because in God there is no partiality.

This past week, during a shared homily at Mass at the Dorchester Penitentiary, one of the inmates looked at his prison-assigned clothing and then at how everyone else was similarly dressed and said, “We all wear the same blue outfits. God has no favorites.” He wasn’t putting himself and the other inmates down, for that would be false humility. He was speaking from a place of truth, the same place of truth the tax collector spoke from when he prayed to God in the Temple. The tax collector returned home justified. Joseph, the inmate, went back to his cell justified.

Humility is not about putting ourselves, or anyone else for that matter, down. Humility is about authenticity. It’s about growing into and living from our true and authentic self, the self made in the image and likeness of God.

Like with all of Jesus’ parables, Jesus turns the tables on his audience. He always walks away leaving us scratching our head and pondering how in this seemingly innocent parable, he was talking about each one of us. At a recent workshop, the presenter reminded us through a story of her own, that there is not “Us” and “Them”; there is only “Us”. We all wear the same blue outfits. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female—for we are all one in Christ Jesus (Galatians 3:28).

Fr. Phil Mulligan

OCT

2022

About the Author: