A boy goes up to his father and says, “Daddy, how does the sun, the moon, and the stars stay up in the sky without falling to earth?” The father answered, “I don’t know, son. “Daddy,” asked the son a second time, “How does winter turn into spring and spring turn into summer?” “I have no idea how that works, son.” “Daddy, how does a bear know it’s time to hibernate in the winter? And how does it know when to come out of its den in the spring?” “Son, I haven’t got the faintest idea how a bear knows that.” “Daddy,” the boy continued, “thank you for allowing me to ask you so many questions.” “No problem, son” said the father, “how else are you going to learn?”

Although the father is kind of useless, in that he doesn’t provide his son with a single answer to his questions, there’s still something I like about the father. Maybe it’s his honesty. Maybe it’s his ability to create a space where questions can be asked without dismissing his son. One way or another, it makes me think of Easter, our greatest feast day.

The resurrection of Jesus is the central story of our faith. Yet, it does not come with packaged answers. Fr. Richard Rohr writes in one of his books: “When a Christian needs to ensure outcomes, you know they are outside the realm of faith. When we do not need to control the future, we are in a very creative and liminal space where God is most free to act in our lives. Faith seems to be the attitude that Jesus most praises in people, maybe because it makes hope and love possible.”

In that quote, Fr. Richard mentions a thing called liminal space as being a creative space within us where God can do God’s best work. It might be the place where God can do God’s best work within us, but it’s also the hardest place for us to be, even for the shortest time. It’s a hard place to be, because when you’re in liminal space you are betwixt and between. Another good word for liminal space is threshold. The threshold is the doorway between one room and another. In the threshold, you’ve left one room, but you’ve not entirely entered the next room. When you are in liminal space you’ve left one job, but you’ve not yet started another one. In liminal space, a significant relationship has come to an end, maybe through separation or divorce, but you have not yet found the healing to move on completely. In human development, puberty is a liminal stage. You are no longer a child, but you are not yet a fully developed adult. The greatest example we have of liminal space in the natural world is the transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly. The transformation happens in liminal space, in the cocoon, when the caterpillar can no longer crawl, yet because it is not yet a butterfly, it also cannot fly. It’s betwixt and between.

It’s a hard place to be, because we feel like Jonah in the belly of the whale; we are not in control of where life, this bloody whale, will take us. Jesus in the tomb is an example of liminal space. He is no longer walking the earth, nor is he among us as the Risen One. He is betwixt and between.

When we are in liminal space, the tendency is to run back to the past, to a security we once knew. The future is too uncertain, and we find ourselves saying, “Better the devil we know than the devil we don’t know.” Or, the opposite happens; we want to run ahead as quickly as we can. Have you ever caught yourself saying, “I wish I could just jump ahead a week, because I really don’t want to face what’s coming my way this week”? Or maybe a person has lost their spouse and wishes they could just jump ahead a year or two because the present is so painful.

Like I said, being in liminal space is the hardest place to be, yet it’s the place where all creativity and transformation arise from. That’s why I like Mary Magdalene as she attempts to puzzle the mystery of Christ’s resurrection in her own mind. Unlike Peter and John, who, after looking into the empty tomb, simply returned to their homes, Mary sticks around the empty tomb. She has the courage to stay in liminal space even though it was breaking her heart to do so. She doesn’t need to have all the answers, all the dust settled, although a part of her would like to have a few answers. She doesn’t have to have everything black and white; she knows she is standing in a grey zone. In liminal space, we don’t have the answers, so we learn to call on God all the more. When you can’t change something, or fix it, or undo it, or re-do it, or even understand why it ever happened to you in the first place, you are in liminal space. Stay there like Mary Magdalene does, as difficult as it may be, and something creative will happen.

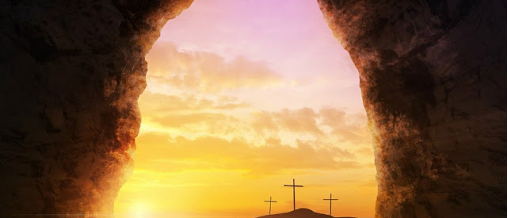

The Easter story starts off with the words, “while it was still dark.” Morning has not yet broken, but it’s on the cusp of breaking. Morning twilight is what we call dawn, just before sunrise. Evening twilight is what we call dusk, just after sunset. The resurrection story happens when there’s just a little light. In that hint of light, Mary Magdalene remains until she hears Jesus call her name. In that moment she is transformed.

Recall, if you will, how the Triduum started. It started with a first reading from the Book of Exodus on Holy Thursday. God instructed our Hebrew ancestors to slaughter a lamb at twilight. What is twilight? It’s liminal space. The Hebrew people were on the cusp of freedom, but they weren’t quite there yet. The had to dare leave the only life generations of them knew, the life of slavery, and venture off into the great unknown where God would lead them. This took courage and lots of faith. Where did they go? Into another liminal space, the desert, where they wandered for 40 years. Until they made it to the Promised Land, they were homeless. Sure they were no longer slaves in Egypt, but they were still homeless. No wonder so many of them wanted to run back to Egypt. The devil you know is better than the devil you don’t know. Many of them wanted to cling to the past much like Mary Magdalene also wanted to cling to Jesus.

In the liminal spaces in our own lives, when we feel like we’re in the belly of the whale or in the darkness of the tomb, we need to hear two things. We need to hear the reassuring voice of Jesus calling us by our name just as he called Mary by her name. We also need to hear, “Do not hold on to me.” If we do not hold onto Jesus in the flesh, we will be able to welcome him in the only way he can come to us—in his Spirit. With his Spirit in us, we will leave the twilight behind and walk into the glorious light of resurrection, a resurrection that is both his and ours.

Fr. Phil Mulligan

APR

2023

About the Author: