As we say “good-bye” to gospel writer Matthew, who has been our guide this last liturgical year, we end with a reading that summarizes Jesus’ entire life among us. If we were to read and try to apply just this gospel reading alone, I’m convinced it would be more than enough to convert us and change the world forever. When I take this gospel passage seriously in my own life, I realize I have more blow opportunities, more sins of omission, more good things I could have done or should have done than I care to admit. I have to concede, like Jesus’ apostles, “Lord, this is impossible.” More importantly, I need to hear Jesus say to me, as he said to them, “You’re right. It is humanly impossible, but with God, all things are possible” (Mt. 19.26).

If that’s the case, then we need the Holy Spirit big time. The Holy Spirit does three things in us and not in the order I like. Firstly, the Spirit confronts us (Jn. 16:8)—tells us the truth about the illusions in our lives. We all live with a certain number of illusions. Secondly, the Spirit converts us—tells us about leaving the illusions behind and living in the Truth. Thirdly, the Spirit consoles us. I prefer a Spirit that bypasses confronting me and converting me and simply delights in consoling me. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way.

The Spirit firstly confronts us, or as some translations of the Bible put it, “convicts us.” The Spirit of Truth, that Jesus promised us and has given us, confronts me each time I pray the rallying cry of Advent: Come, Lord Jesus! The Spirit of Truth, that Jesus promised us and has given us, confronts me each time I pray, “May your Kingdom come.” I want the Lord Jesus to come, but on my terms. I want the Kingdom of God to come as long as I can also keep my little kingdom. When I refuse to say, “Come, Lord Jesus” with openness and honesty, I am refusing to hold out for the big picture, God’s Kingdom, and I settle for something that can never truly satisfy me.

In place of God’s Kingdom, I want a self-made kingdom where all my anxieties are taken away, where I can justify why I’m right, and why I deserve a better lot in life. When I think like that, I inadvertently push away God who entered into the imperfect world I refuse to accept. Jesus came and he still needs to come. He will come when I stop desiring perfection of others or of life in general. In the embrace of all that is imperfect, incarnation happens, the Lord Jesus enters. It’s the only world Jesus can enter. By confronting me, the Spirit is inviting me to let go of my little world, my demands on others, and to stay open to a much larger kingdom that is yet to come.

The second thing the Holy Spirit does in our lives, besides confronting us, is converting us. A conversion is a 180-degree turn. It’s an emptying of ourselves, of our illusions, our titles, our status, and even of our opinions that some of us think are worth dying for. In its place we stand naked before God know, finally, that who we are at any given moment, is enough. True conversion is not for the faint of heart. True conversion is the pursuit of the True God, and not the god of my convenience, and the pursuit of the True Self, not some persona we keep propping up. In the end, when you find the True God or the True Self, you automatically find the other.

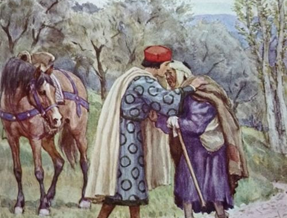

Even the great saints, like St. Francis of Assisi, had to allow the Spirit to convert him. One of the turning points in Francis’ life happened after he came back from the Crusades. He left as the son of a rich merchant wanting for nothing in life, hoping to come back from the war as a hero of the people, a defender of the Catholic faith. Instead, he returned to Assisi with what we might call P.T.S.D. (post traumatic stress disorder). Everything he thought was important, everything he thought was worth fighting for, or even dying for, now meant nothing to him. Through sickness, depression, and a lot of soul-searching as a prisoner of war, the Spirit was bringing about a permanent conversion in Francis’ life. Worse than the horrors of war, the thing Francis feared the most was leprosy. One day, while riding his horse, Francis encountered a leper. He spurred his horse onward in order to escape what he called, “a disgusting sight.” Then, in a moment of God’s doing and not his, he was filled with remorse and God’s grace. So, he turned his horse around and dismounted. He then gave some money to the leper, hugged him, and kissed him. He then got on his horse again and left, his heart filled with gladness. While he was galloping away, he turned to say goodbye, but the leper was gone. The man had mysteriously disappeared. This experience was fundamental for Francis in shaping who he was to become. He recognized it was God who was acting there in the guise of a leper. He began to feel a deep inner kinship with the whole of humanity, but especially with the poor and the outcast. Francis’ new understanding of the human person is fundamentally identical to what we find in today’s gospel.

Conversion, this second movement of the Spirit in our lives, is never where we initially want to go, but it’s always where we need to be. I suppose I’ve had ample opportunities to experience conversion in my life, ample occasions to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, to clothe the naked, and to even embrace the leper. Leprosy, what we call Hansen’s Disease, was agonizing not so much physically but because of pain it caused socially. Lepers were considered taboo, contagious, dangerous and should exist only on the outer fringes of society for the benefit of the rest of us. Who are the lepers in our society? Who are the ones we give the message, “You’re not doing it right” or “You’re not acceptable as a member of society”? What areas of our lives still need the Spirit of conversion?

Key to Francis’ conversion was the fact that he saw the leper as his equal. When we see the hungry, the thirsty, the naked, the lonely, the sick, the imprisoned, the marginalized, as our brother or sister equal in the eyes of God, conversion—in that moment—is taking place within us. When conversion happens within us, a conversion that might take a long period of time, we feel the consolation of Spirit inside us. That’s the third action of Spirit; the Spirit consoles us.

A rabbi addressed his students with the question, “When can you tell the night has ended and the day has begun?” One of the rabbi’s students offered the reply: “When you can see a tree in the distance and tell if it is an apple tree or a pear tree.” The rabbi answered, “No.” Another student responded: “When you can see an animal in the distance and can tell if it is a sheep or a dog.” Again, the rabbi said, “No.” “Well,” his students protested, “When can you tell, that the night has ended, and the day has begun?” And the rabbi responded, “When you can look on the face of any man or woman and see that he is your brother, that she is your sister—because if you cannot, no matter what time of the day it is, it is still night!”

The older I get, the more I realize that those relegated to the margins of society have a hidden grace that those living in the comfortable middle cannot give me. If I don’t dare to go to the edges, I will not be able to say this Advent, “Come, Lord Jesus” or “May your Kingdom come” with any integrity.

Fr. Phil

NOV

2023

About the Author: