This is the third Sunday we have a parable set in a vineyard. Vineyards are places where both labor and love take place. Biblically speaking, vineyards are where you earn your keep by working hard, and they are places of romance and courting. Labour and love. These three last Sundays have given us stories of labour but not so much love. You may recall the parable from a couple of weeks ago of the vineyard owner who hired labourers at different times during the day and payed each of them a full day’s wage. Everyone got the maximum pay due to the generosity of the owner, and everyone was perfectly happy with their pay until one person compared himself to another and the jealousy started and the trade union was up in arms.

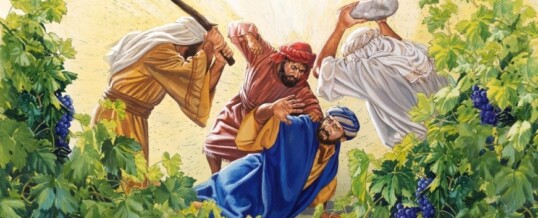

Today we are in the vineyard again. This time the tenants have moved passed comparison and jealously straight into the world of violence. Violence is always one inch under the surface in each of us, although none of us would admit to being a violence person. This is a parable that mentions seizing, beating, stoning, and killing; we are spared nothing with this story. It all starts with jealousy, greed, and a sense of entitlement. If jealousy and greed are the source of such violence, what is the source of jealousy and greed themselves? Where do they come from? They come from a lack of gratitude. These vineyard parables raise a lot of questions in me like: Why is it we are rarely content with the grass on our own side of the fence? Why is it we are perfectly content with our dining room set until we are invited out to dinner to a friend’s house? Why is our car absolutely fine until we come back from holidays where we spent a week driving a new rental car? Another question: Can we hold onto something for a while, appreciate it, and pass it on without having the need to possess it? For instance, can we enjoy a piece of art in a museum, where others can enjoy it too, or do we have to own it just for ourselves?

We were never, from the opening lines of the Bible, made “owners” of the earth, or anything else for that matter, but we were made “stewards”. A steward does not own anything but is entrusted with the care of something until it can be given back to its rightful owner. The owner has placed trust in us, and we want to be worthy of that trust. If you are anything like me, you tend to care for something, lent to you by another, even more than you care for something of your own. I would feel much worse about putting a dent in a car that someone loaned me than putting ten dents in my own. I do not even know if I would dare to drink coffee in someone else’s car for fear of spilling it. When you think in those terms, you are thinking more like a steward and less like an owner. You are beginning to appreciate that something has been entrusted to you.

Back in 1992, the American bishops put out a pastoral letter on stewardship. In it they write: a steward is one who 1) receives God’s gifts gratefully, 2) nurtures them responsibly, 3) shares them justly and generously, and 4) returns them to the Lord abundantly. The whole thing starts with receiving God’s gifts gratefully, the very thing that goes off the track in these vineyard parables. No wonder they end in violence. When you do not start with gratitude, you tend to start with entitlement. And if anyone gets in the way of what I am entitled to, I can justify my violence toward them. So goes the logic.

When you start with gratitude, you know someone has placed something in your hands that you did not create through your own hard work. Think of the Eucharistic prayers at Mass, particularly when the bread and wine are first placed upon the altar. The priest starts this way while lifting up the bread: Blessed are you, Lord, God of all creation, for through your goodness we have received the bread we offer to you: fruit of the earth and work of human hands, it will become for us the bread of life. Notice, that before anything is the work of human hands, it is first the fruit of the earth. It is all given. Before we can receive anything, it is God who first offers it. The priest continues in the same way with the wine: Blessed are you, Lord, God of all creation for through your goodness we have received the wine we offer you: fruit of the vine and work of human hands, it will become our spiritual drink. Before the fruit becomes the work of human hands, it is already the fruit of the vine. It is already given. Everything in life is first given, then it is work on by our hands.

You may know this already. Before Native North Americans would kill an animal, they would do three things: 1) thank the Creator, 2) promise to use as much of the animal as possible, and 3) ask the animal for its forgiveness. What a different way of seeing stewardship! It never asks the question: What’s in it for me? It never assumes ownership or entitlement.

I wonder where they got this vision? Perhaps through a vision quest. All young men in First Nation bands had to be initiated by elder men or the assumption was they would not know how to be men at all. Without these formal, deliberate, and sometimes brutal rituals these young men would grow up and abuse women, abuse the earth, and abuse power. During the initiation rite, they were to go off by themselves for extended periods of time without food, without water, and without easy answers. They had to learn to sit in silence, sometime in their own grave, until they longed for a word of wisdom or a vision that came from beyond themselves. This was assumed to take at least three days and sometime up to 15 days. If they did not get a vision or a word from the Great Spirit, they would not be allowed to return to the community to marry, to father children, or to take any role of responsibility within the community. The elders were entrusting these newly formed men to work for the common good and not for their own personal advancement.

In short, they had to learn to be good stewards caring for the earth and all its creatures including its human creature. Similarly, Paul, the Christian persecutor turned saint, had to go blind for three days as part of his conversion (Acts 9: 8-9). Zechariah, John the Baptist’s father, had to go dumb for a while before God allowed him to speak not his own word but God’s word (Lk. 1:20). Perhaps we need our own form of a vision quest as a Church where we are blinded or made dumb, at least for a while, until a greater vision for our world is hungered for and is given to us from beyond ourselves. The vineyard of the Lord is not simply Jesus’ own Jewish people nor the Church. The vineyard is likely all of creation over which God has placed us as stewards.

Fr. Phil

OCT

2020

About the Author: