For all their goodness, intelligence, and enthusiasm, many in the younger generation lack patience. For the most part, they see little or no value in “delayed gratification.” In time they will learn, what we all had to learn, that some things really are worth waiting for. Learning this lesson will be particularly painful and frustrating for the generation who grew up in a world of fast food, high-speed internet, and smart phones. With the invention of the credit card in the late 1950s, gone were the days when you bought something because you patiently saved up for it. Society lost something with the convenience of that little piece of plastic. We always cherish and appreciate those things we had to work for over and against the things that were simply handed to us. The easy-come-easy-go mentality has never produced grateful people or people of integrity, nor will it ever.

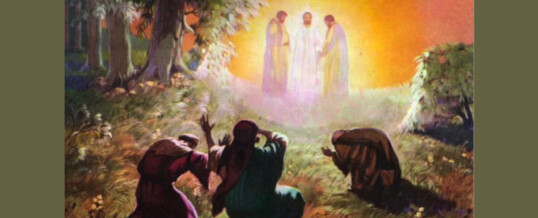

Perhaps this is what Jesus was getting at when he told his apostles, Peter, James, and John not to tell anyone about the vision they experienced on the mountain of transfiguration, until after the Son of Man has been risen from the dead. The glimpse of the glorified Jesus was a gift given to them and could easily fall into the category of easy-come-easy-go. They hadn’t worked for it, but Jesus wanted them to do some work with it. Faith is given to us, but we are also called to work with it, to foster it, to nurture it. Bread is given to us from the goodness of God, but it is also the work of human hands.

Fr. Richard Rohr, the great Franciscan, speaks in a similar vein. He reminds us that God was revealing God’s self to humanity long before the birth of Jesus and long before the Bible was written. The first Bible, the first divine revelation of God, is the Bible of nature. Until recently, this insight went right over my head. Perhaps a little bit more time in nature, the place where Jesus constantly returned to, and I would have gotten the revelation of God a lot quicker. Fr. Richard goes on to say, “Words give us something to argue about, I guess. Nature can only be respected, enjoyed, and looked at with admiration and awe. Don’t dare put the second Bible in the hands of people who have not sat lovingly at the feet of the first Bible. They will invariably manipulate, mangle, and murder the written text.”

Now I’m beginning to understand why Jesus admonished his apostles not to speak about the vision until a later date, a time after the Son of Man had been raised from the dead. Jesus didn’t want his apostles to manipulate, mangle or murder the experience of his transfiguration. Instead, he wanted them to sit with this experience, to savour it, to live it, to appropriate it, and finally to speak about it. Jesus wanted his apostles to speak only after the Son of Man had been raised from the dead. Jesus, the pattern of all our lives, first had to suffer and die before being raised from the dead. He had to experience the worst before he could proclaim the best. At some point, in each of the four gospels, Jesus simply stops talking about suffering, dying, and being raised from the dead. He just gets on the road to Jerusalem and enters into his passion, death, and resurrection. He knew, he himself had to experience suffering, death, and resurrection before he could credibly preach about it. Words are cheap, but actions speak volumes.

Jesus never once asked to be admired or worshipped, only to be followed. When we follow him, we follow him through his suffering, death, and resurrection. By doing so, we must be willing to suffer ourselves; we must be willing to go down the mountain. He ultimately wants us to share in his resurrection, his glory, his ascension into heaven. Unfortunately, it doesn’t come about without first going through our own pain, suffering, and death. Unless the grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains only a single grain (Jn. 12:24).

Pain, suffering, patience, and delayed gratification have something to teach that we could never learn if we avoid them. In my impatience, I want the answers now. I want all the dust to be settled. I don’t want to live with ambiguity. I want things to be black and white. I want to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and be the ultimate judge of what is truly good and truly evil. That way I can gather to myself all that is “good” and push away anything and anyone I deem “evil.” Yet, God has another plan, a better plan, a plan where I have to go down the mountain into the murkiness, the messiness, the ambiguity of life and live there in trust. It’s only there where I learn to finally call on God. It’s only there where I have to accept that the unfolding of God’s plan in my life is infinitely better than anything I tried to engineer myself.

Here’s a little story about going down the mountain, about delayed gratification, and about the wisdom of God that unfolds in its own time.

There was a farmer who knew the yin and yang (seemingly opposite and contrary forces) of things. Wealth in his day was measure by how many horses you owned. One day his lone stallion ran away. His neighbour expressed to the farmer how bad he felt for him. The farmer responded with, “Who knows what is truly good and truly bad?” The neighbour thought to himself, “This is really bad.” Shortly afterwards, the stallion returned accompanied by three mares! The farmer shut the gate keeping them all inside. The neighbour, this time, expressed his joy at the good fortune of the farmer. Again, the farmer responded, “Who knows if this is truly good or truly bad?” The neighbour thought to himself, “This is definitely good.” One day, one of the horsed kicked the farmer’s son injuring him permanently. The neighbour heard about the accident and expressed his sorrow to the farmer over this tragedy. The farmer responded, “Who knows if this is truly good or truly bad?” The neighbour thought to himself, “This is definitely bad!” Soon war breaks out. The neighbour’s son is conscripted into the army. The farmer’s son, because he was now considered an invalid, was not conscripted for the war. The neighbour said to himself, “Who knows if this is truly good or truly bad?”

Fr. Phil Mulligan

MAR

2023

About the Author: